|

| Karel van Wijnendaele |

On this day in

1913, the inaugural

Ronde van Vlaanderen was held. Like many of the older cycle races, it was organised to promote a newspaper, in this case the Flemmish

Sportwereld. Only 37 riders turned up to race (some sources say 27), a major disappointment for the paper's co-founder and race organiser Karel van Wijnendaele (real name Carolus Ludovicus Steyaert, 16.11.1882 - 20.12.1961 - he took his pseudonym from the name of the village where he was born, ) who had become editor on the 1st of January that year. "Sportwereld was so young and so small for the big Ronde that we wanted. We had bitten off more than we could chew," he later said. "It was hard, seeing a band of second-class riders riding round Flanders, scraping up a handful of centimes to help cover the costs. The same happened in 1914. No van Hauwaert, no Masselis, no Defraeye, no Mosson, no Mottiat, no van den Berghe, all forbidden to take part by their French bike companies."

When van Wijnendaele was eighteen months old, his father died - which left his mother to raise her fifteen children alone. This meant, of course, that as soon as the boy reached fourteen years and could leave school he needed to find work - which he did, carrying out odd jobs for a baker and looking after cows, washing bottles and doing other odd jobs for rich French-speaking families in Brussels. He hated the way they looked down on him for his poverty, but their prejudice was what drove him on to make something of himself and, like so many others in the early days of the sport, he turned to cycling as a way to make extra money. "Being born into a poor family, that was my strength," he later said. "If you're brought up without frills and you know what hunger is, it makes you hard enough to withstand bike races." He must have been an exceptionally bright lad - his education would have been extremely basic, but when he realised he was never going to make his fortune from racing he turned to writing about it instead. His skill as a writer was good enough that by 1909 he was cycling correspondent to two national titles.

In that first year, the race started in Ghent with the parcours consisting of a 324km loop through Flanders and back towards Ghent where it ended at a wooden track at Mariakerke, running through Sint-Niklaas, Aalst, Oudenaarde, Kortrijk, Veurne, Ostend, Torhout, Roeselare and Bruges along the way. As was standard in races of the time, all riders were expected to be entirely self-reliant and, permitted no assistance from team vehicles or mechanics, had to carry spare parts and perform all roadside repairs themselves. The prize fund added up to 1,100 Belgian francs and the money

Sportwereld made from the event covered less than half that cost.

|

| Paul Deman, 1889-1961 |

The winner - with a time of 12h3'10" - was 25-year-old Paul Deman, who would also win Bordeaux-Paris the following year before becoming involved in espionage during the First World War when he acted as a cycle courier smuggling top secret documents into the Netherlands, which remained neutral. He was eventually caught by the Germans and imprisoned in Leuven to await execution by firing squad - fortunately, the Armistice was declared just in time to save him and he returned to cycling; winning Paris-Roubaix in 1920 and Paris-Tours three years later.

Despite van Wijnendaele's dismay, word had spread by 1914 with riders generally appreciative of the race and in 1914 47 showed up. The French teams still forbade their members from entry, but Alcyon's Marcel Buysse - a Belgian himself - recognised that the race was destined for great things and refused to pay heed; entering and winning the second edition. In time, the Ronde became a symbol of Flemmish national pride and so successful that the enormous crowds of spectators would cause problems, and the race is now perhaps the second most popular of the Monuments after Paris-Roubaix which it precedes by one week on the racing calendar.

|

| All but forgotten: Luigi Annoni |

The

Giro d'Italia started on this day once, in

1921, when it covered 3,107km in ten stages. Costante Girardengo, then aged 28 and arguably the strongest cyclist the world had yet seen, was by far the favourite and led the General Classification from the start of the race after winning the first four stages. Stage 5, however, was a complete and unmitigated disaster - having suffered a series of mechanical failures, he decided he'd had enough, dismounted, drew a cross on the road and declared "Girardengo si ferma qui" ("Girardengo stops here"). Gaetano Belloni had caught him up in the GC the day before, so the leadership went to him when he won the stage and he kept it the next day too despite losing the stage to Luigi Annoni. However, Giovanni Brunero won Stage 7 and then rode carefully; keeping out of harm's way but ensuring he completed each of the remaining three stages with a time good enough to remain in front overall. Annoni won Stage 8, then Belloni won Stage 9 and 10 - but neither could catch Brunero, who won with an advantage of 41".

Geraint Thomas

Born in Cardiff on this day in 1986, Geraint Thomas began cycling competitively when he was ten years old with a local club, the Maindy Flyers - named after a Cardiff velodrome with a famous uneven track caused by subsidence. He also raced for the Cardiff CC and Just In Front clubs with whom he began to enjoy some success including a National Junior Championship and a silver medal at European Championships, which earned him a place on British Cycling's Olympic Academy. In 2004, he became World Junior Scratch Champion, then in 2005 he took the National Elite title for the same event and shared gold medal for the team pursuit race with Mark Cavendish, Steven Cummings and Ed Clancy. That same year, his career almost came to an early end: during a training ride in Sydney: a shard of metal lying in the road was thrown into his wheel when the rider in front of him him hit it, causing him to crash - onto the metal, which ruptured his spleen and caused massive internal bleeding.

|

| Geraint Thomas |

His spleen had to be removed, but he made a full recovery and, two years later, entered his first Tour de France with Barloworld; the first Welshman in the race since Colin Lewis in 1968 (though since Lewis was born in Devon, his status as a Welshman is a little shaky). He was 140th, just one away from Lanterne Rouge, but had finished in the top 20 for two stages - but merely finishing a Tour is an achievement, especially if it's your first and you're

Benjamin du Tour (the youngest rider in the race). He chose to stay away the next year, instead riding the Giro d'Italia before returning to Britain in order to train for the Beijing Olympics where he, Ed Clancy and Bradley Wiggins won the Team Pursuit. His 2009 season was severely limited after a crash during the individual time trial at Tirreno-Adriatico when he misjudged a corner, hitting crowd barriers and fracturing his nose and pelvis. He returned to competition late in the year to take 6th place overall at the Tour of Britain and, on the 30th of October, set a individual sprint world record time under current rules at the UCI World Track Championships by finishing the 4km in 4'15.105" - 3.991" slower than the fastest time ever recorded, set by Chris Boardman thirteen years earlier but using a riding position since banned under international competition rules. At the end of the year, he announced that he would be leaving Barloworld to ride for the new British team Sky.

His first season with Sky would be a good one, kicking off with team time trial victory at the Tour of Qatar before he went on to four consecutive top ten stage finishes at the Critérium du Dauphiné and then the National Road Race Champion title. He also rode the Tour de France again, finishing the prologue in fifth place, second on Stage 3 and leading the Youth Category (in which he would eventually come ninth overall) for a short time. 2011 got off to an even better start with second place at the Dwars door Vlaanderen, possible indication that he may have the makings of a future Classics winner, then in May he won the Bayern-Rundfahrt - his first professional stage race victory and the first time the race had ever been won by a British rider. He would wear the white jersey again at the Tour that year after finishing Stage 1 in sixth place, then kept it until Stage 7 after Sky finished the second stage team time trial in third place - he would be one of several Sky riders to lose significant time in that stage when they waited for team captain Bradley Wiggins who had been in a crash and, it turned out, would not be able to continue. On the Hourquette d’Ancizan as the race entered the Pyrenees, Thomas led an early break and would twice stare injury in the eyes, losing control and very nearly crashing twice within just a few seconds - his determination that day earned him the Combativity award. For 2012, he plans to take part in the Giro d'Italia but will then concentrate on track cycling in the run up to the Olympics.

Thomas has been a vocal opponent of doping in cycling. In 2008, when Barloworld team mater Moisés Dueñas was thrown out of the Tour for France due to a positive test for EPO, Thomas was forthright in his opinions. "Duenas, when I last heard, was facing a five-year prison sentence in France, which I hope he gets," he told the BBC. "It’s about time people realised it can’t happen anymore. I guess you will always get people who will try to cheat the system, not just in sport but in everyday life. Saying that, if someone is fraudulent in a business, wouldn’t they be facing a prison term? I don’t see how riders taking drugs to win races and lying to their teams is any different. Bang them up and throw away the key!" He is also proud of his Welsh roots - when told that flags of non-participating nations would not be permitted at the 2008 Olympics (Wales, as a part of the United Kingdom, counted as such; though non-recognised might have been a more accurate term), he said: "It would be great to do a lap of honour draped in the Welsh flag if I win a gold medal, and I'm very disappointed if this rule means that would not be possible."

Ian Stannard

Thomas' Sky team mate Ian Stannard shares his birthday but is one year younger. Born in Chelmsford, Great Britain, he made his professional debut as a trainee with T-Mobile in 2007 having been invited to join the team when managers chopped out several older riders in an attempt to move on from a series of doping scandals and present a more youthful squad at that summer's races. However, he would remain with them for less than a year; moving on to Landbouwkrediet-Tönissteiner in 2008 - the year he took part in the Tour of Britain and came third overall, riding for an unusual GB national team.

In 2009 he switched again, this time to ISD (now Farnese Vini-Selle Italia), and rode the Giro d'Italia - his first Grand Tour, where he came 160th. At the end of the season he announced that he would be moving to Sky for 2010, with whom he immediately revealed himself to be a Classics specialist of some note when he took third place at Kuurne-Brussels-Kuurne.

Daan de Groot

Daan de Groot, born in Amterdam on this day in 1933, won Stage 13 at the 1952 Tour de France after using what can only be described as unusual tactics. The stage ran for 205 flat kilometres between Millau, now world famous for its 343m tall Viaduc (the tallest bridge in the world), and Albi, home to one of the world' most spectacular cathedrals (which began life in 1287 as a fortress and remains the largest brick-built structure in the world). Both lie in the Tarn, which is in that part of Southern France that's just a little too far from the Mediterranean and Atlantic to enjoy cool breezes and it gets very, very hot indeed - as it had done that day, and the peloton were suffering.

|

| 1933-1981 |

De Groot had been dropped by the peloton and many of the other riders in the autobus must have thought the sun had gone to the Dutchman's head when he suddenly stopped, got of his bike and dived into a field of cabbages - the Dutch are, after all, not well-accustomed to searing heat. A few were probably convinced when he picked some leaves from one of the plants and wrapped two around his neck and placed one underneath his casquette.

However, he was a wiser man than they thought. With the cool, fleshy leaves protecting him he recovered and was able to sprint off to catch the peloton, then gradually made his way up to the front. Realising that the heat had now had a similar effect on the entire pack, he attacked and nobody could chase him down. Someway up the road, the blackboard man told him that he had an advantage of

treize minutes, half an hour - but, as he spoke very poor French, he thought he had three minutes and accelerated, going on to win the stage by 20 minutes.

De Groot's wife died in 1981. A year later, aged 48, he committed suicide.

Joseph M. Papp

Born in Parma, Ohio on this day in 1975, Joe Papp began cycling competitively in 1989 and joined the US National Team five years later and achieved some impressive results. In 2006, a sample he provided at the Tour of Turkey tested positive for testosterone metabolites and he received a two-year ban - unusually, it was also ruled that all his results since 2001 would be disqualified, which led to widespread complaints from fans.

However, while testifying in the Floyd Landis case, Papp confessed to having been a part of an extensive doping program that had been in place for some time and listed the many drugs he and other cyclists regularly used, also admitting that he had almost lost his following a relatively minor crash that caused massive internal bleeding due to his use of EPO. As a respected cycling author, he has since become considered something of an expert on doping - his detailed descriptions of what cyclists use, when, why and what it does to them enabled WADA to successfully argue against Landis' claim that he would not have used testosterone at the 2006 Tour de France because it would not have helped him improve his performance. While he was quick to testify against Landis, he was also one of the first to extend the hand of friendship in 2010 after the Pennsylvania-born rider finally decided to come clean. That same year, Papp was charged with distributing banned performance drugs, a charge to which he pleaded guilty before naming 180 athletes to whom drugs had been supplied. The case was eventually sealed, indication that related cases are still in progress, and in 2011 Papp was handed a three-year suspended sentence.

Today, Papp gives many speeches each year in which he outlines the dangers of doping in an attempt to discourage others. He has never officially retired from cycling and as such remains on the US Anti-Doping Agency's test pool list, having to provide them with accurate details of his whereabouts for a period of one hour every day of the year. He has never missed a test.

|

| Georg Totschnig |

Born in Latenbach on this day in 1971, in 2005

Georg Totschnig became the first Austrian to win a stage at the Tour de France since Max Bulla in 1931 when he beat no less a figure than Lance Armstrong. He'd been part of a break that had escaped early in Stage 14, then he, Walter Bénéteau and Stefano Garzelli split the group when they rode off alone. Bénéteau and Garzelli fell back on the final climb to Ax 3 Domaines, but Totschnig kept going hard and held Armstrong off all the way; eventually crossing the line with a 56" advantage. His achievement earned him the Austrian Sportsperson of the Year award.

Branislau Samoilau, born in Vitebsk on this day in 1985, won the Under-23 Liège-Bastogne-Liège in 2004, was Belorussian Under-23 Time Trial Champion in 2005 and 2006, then took the Elite title in 2007, 2008, 2009 and 2010. He's also not a bad stage racer, having come 22nd overall at the 2007 Giro d'Italia and 16th overall at the 2011 Tour de Suisse. Now riding with Movistar, he may well develop into a talented all-rounder in the coming years.

Erki Pütsep, born in Jõgeva on this day in 1976, was Estonian Road Race Champion in 2004, 2006 and

2007.

Jean-Pierre Danguillaume, born in Joué-lès-Tours on this day in 1946, won seven stages at the Tour de France (Stage 22 1970, Stage 18 1971, Stage 6 1973, Stages 17 and 18 1974 and Stages 11 and 13b in 1977) in addition to the Peace Race (1969), GP Ouest-France (1971), the Critérium International (1973) and numerous other races over the course of his eight competitive years, riding for Peugeot throughout. Were it not for the fact that his career coincided with that of Eddy Merckx, he might be remembered as one of the great riders.

Evgeni Petrov, born in Ufa, USSR on this day in 1978, became Russian National Time Trial Champion in 2000 - and took the World Under-23 titles for the TT and road race too. He won Stage 2a at the Tour de l'Ain a year later and another National TT title and the General Classifications at the Tour de Slovénie Tour de l'Avenir in 2002. The subsequent few years were less successful until 2007 when he was 7th overall at the Giro d'Italia. In 2005, he was thrown out of the Tour de France after recording a haematocrit reading greater than 50%, deemed likely indication of EPO use or blood transfusion, and was barred from competition for two weeks.

Other births: Orla Jørgensen (Denmark, 1904, died 1947); Juan Alberto Merlos (Argentina, 1945); Marian Kegel (Poland, 1945, died 1972); Wes Chowen (USA, 1939); Tarja Owens (Ireland, 1977); Patrick Jonker (Australia, 1969); Walter Signer (Switzerland, 1937); Igor Patenko (USSR, 1969); Jameel Kadhem (Bahrain, 1971); Tanya Lindenmuth (USA, 1979); Jhon García (Colombia, 1974).

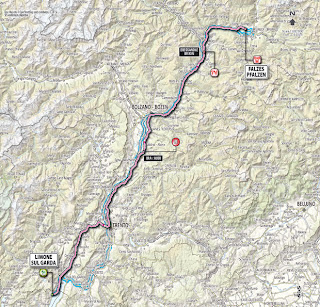

![Image credit: Gazzetta/Giro d'Italia http://images2.gazzettaobjects.it/static_images/ciclismo/giroditalia/2012/tappa_dettagli_tecnici_altimetria_20.jpg?v=%3C!--%20[an%20error%20occurred%20while%20processing%20this%20directive]%20%20--%3E](http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-3YINUEOwJ2A/T8Cu0GmowpI/AAAAAAAAEAQ/3rNnGRHGnMc/s400/GiroST20po.jpg)

.jpg)